In my post about the Lot river I showed a canal lock and a railway bridge and wrote that I had more to say about that. That will be in two parts; firstly I will discuss steam engines and their place at the start of the Industrial Revolution then, in a second post, I will discuss steam locomotives. This is based on my visit to the Science Museum in London.

I am a mechanical engineer and this has a lot to do with my engineering hero, Richard Trevithick, who is hardly known. I will also address some common misconceptions about these two topics.

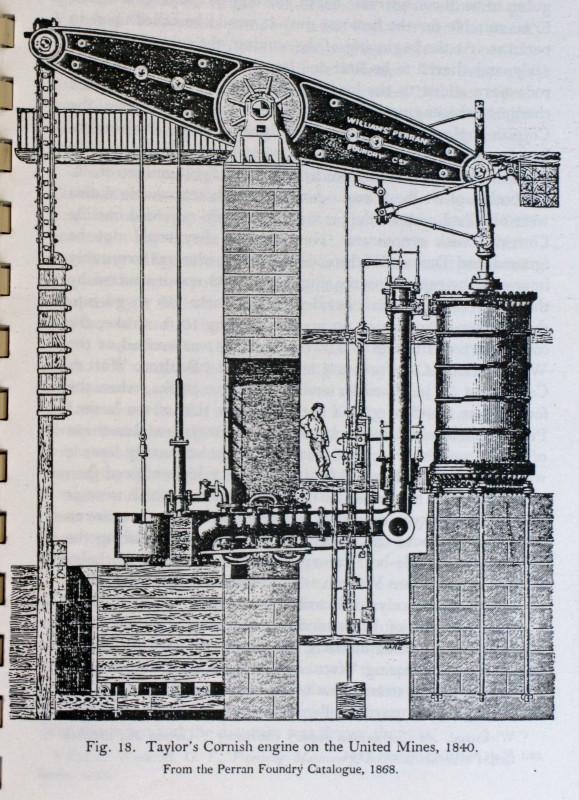

This engraving shows the first useful steam engine. It was designed and made by Thomas Newcomen in 1712; 24 years before the birth of James Watt yet Watt is popularly believed to be the inventor of the steam engine. The size of the person in the picture gives the scale of the machine. That he could have made such a huge machine first time out of the blocks amazes me. There had been nothing like this before besides a demonstration by Papin of steam condensing in a syringe. The steam cylinder was of brass 2,4 meters high by over half a meter in diameter; in other words much bigger than a person. Brass working was well established through the manufacture of cannons. These machines became widely used to pump water out of coal mines. Right from the start Newcomen lays down the design of a beam engine. This machine was so big that it requires a purpose built building. It requires a huge tree be cut and shaped for the massive rocking beam and that person sized pieces be attached to the end and shaped to circular arcs. A big boiler had to be designed and made plus the pipes, the pumps and valves to make it work. All of this with no previous machine like it to guide the inventor. In round numbers that was 300 years ago. Newcomen invented the true ‘steam’ engine. (I will explain below why steam is in ‘’)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newcomen_steam_engine

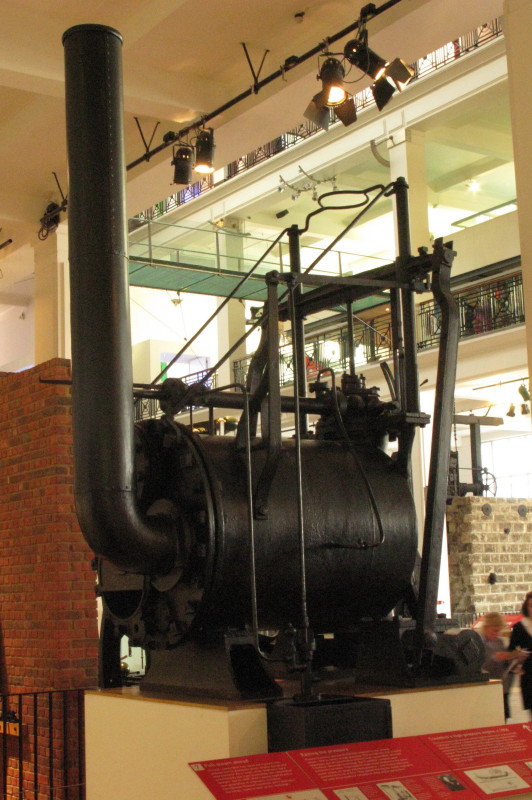

This is a Newcomen engine in the Science Museum in London. It was built in 1791 and was in use for 127 years until 1918 (15 years after the first aircraft flight) which is over 200 years after the first one went into operation. Obviously Newcomen’s design was brilliant to have persisted for that long.

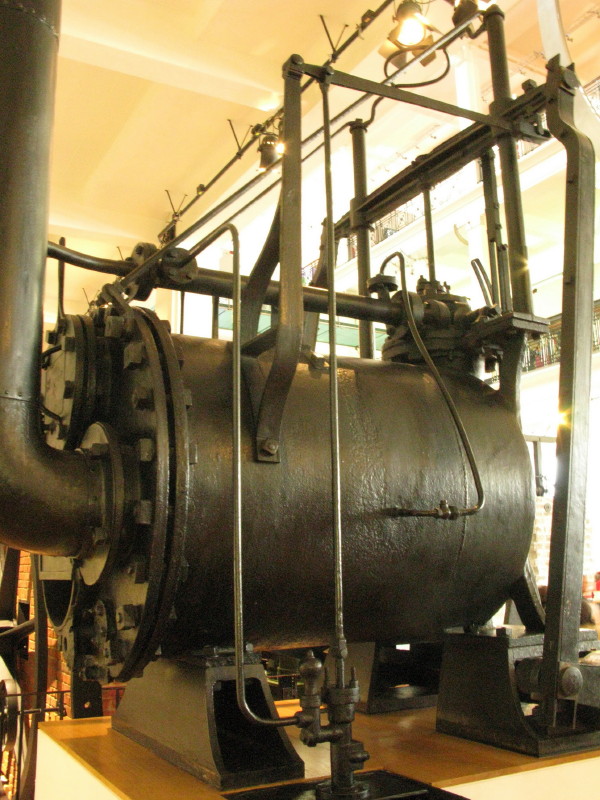

This is the second engine Watt made in Birmingham in 1777.

Watt was a university instrument maker who had to repair a model of a Newcomen engine. He realised that it could be made significantly more efficient by adding a separate condenser. Watt patented his improvement and charged a high royalty for his engines which resulted in the coal mines keeping their existing Newcomen engines until the 1790s when that patent expired. So the Newcomen engines were the predominant type for more than 75 years and the Watt engines came into play 225 years ago..

This Watt engine has a huge gear wheel for driving rotating machinery. Built in 1797. The previous examples all operated pumps which, like a windpump, just made a rod go up and down. To drive industrial machinery a rotating shaft was needed and this Watt did (others also did it but they could not use Watt’s condenser so their machines were hopelessly inefficient in comparison to Watt’s machines). So here we have the real birth of the Industrial Revolution because now it can be powered. Watt is no hero of mine but he did some very elegant detailed engineering. He needed to make his engine dual acting (powered on the up and the down stroke) before it could drive a wheel. That has been done on this engine. So real power came to the Industrial Revolution 200 years ago.

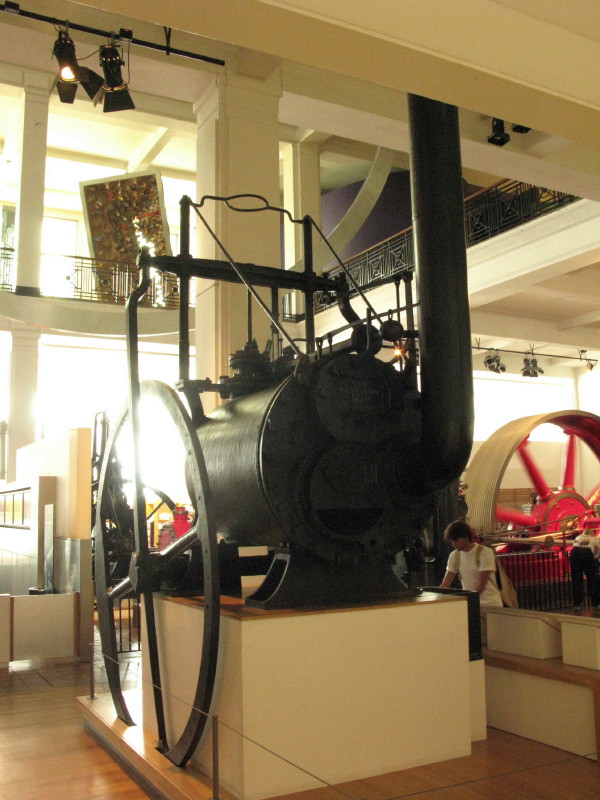

This very large pumping engine is considerably more efficient than a Watt engine. This design was developed by my hero, Richard Trevithick. The Newcomen and Watt engines used steam at atmospheric pressure (so are called atmospheric engines not steam engines). The steam was drawn into the cylinder by the piston rising because of the weight of the pump rod. When the piston was at the top of its stroke and the cylinder was full of steam which was under no pressure the steam inlet valve was closed and cold water sprayed in to make the steam condense back into water. The condensing steam thus pulled the piston down to the bottom of the cylinder (pedants say the atmosphere pushes the piston down). These steam engines were powered by the vacuum created when the steam was condensed. In a Newcomen engine the water was sprayed into the cylinder to condense the steam. In a Watt engine a separate condenser was attached to the cylinder and the water was sprayed into the condenser. Because the cylinder of a Watt engine was not cooled by the water the cylinder remained hot and this saved a lot of steam compared to a Newcomen engine because it took a lot of steam simply to re-heat the cylinder each and every stroke.

What Trevithick did was run his steam at a pressure of 2,5 bar right up to 10 bar. For a big stationary engine like this he retained the condenser so his engine would be 3,5 times as powerful as a Watt engine of the same size when Trevithick used just 2,5 bar pressure. But it is still a beam engine based on the original Newcomen engine of 100 years earlier but now it is a proper steam engine as against an atmospheric engine. Nobody had been able to do anything to progress steam engine design for 25 years while Watt’s patent was valid. Only when it expired about 1800 could others develop his design because he would not allow any other manufacturer to use his separate condenser design (his partner Bolton was the real commercial power whereas Watt was the technical power in the partnership). Trevithick made the first high pressure steam engine in 1799; say 200 years ago.

When I am in London I make a special effort to go and see and touch this. For me personally as a Mechanical Engineer it is the most important artefact of my profession. It is a genuine Trevithck high pressure engine – not a replica. This is the engine which allowed vehicles to be powered – carriages, trains and boats. Here Trevithick uses his higher pressure and omits the Watt condenser. He also dispenses with the huge beam. Using just 3,5 bar up to 6,5 bar pressure Trevithick made the world’s first powered road vehicle in 1801 (Cugnot made something that managed to creep about much earlier but it hardly counts). In 1804 he built the world’s first railway locomotive which pulled 10 tonnes of iron and 5 carriages with 70 men 16 km in just over 4 hours; the world’s first powered train. This one engineer built the first high pressure steam engine which was the basis for mass steam power but he also built the first steam powered road vehicle and the first railway locomotive. Yet he is hardly known at all.

This is what the science Museum says about this particular engine:

Quote:

This is a unique high-pressure steam engine constructed in around 1806 to Richard Trevithick’s design by one of his preferred engine builders, Hazledine and Co. of Bridgnorth in Shropshire. Richard Trevithick was the first British engineer to use ‘strong’ steam - that is, steam at high pressure. Engines like this consumed three times more coal than James Watt’s earlier engines, but could be made far more compact. They were simple and easy to install or adapt, and could be put to an unprecedented range of uses in industry, railways, agriculture and at sea. This engine was found on a scrap heap and restored in 1882.

It is not obvious in the picture quite what is what. The cylinder is set vertically inside the boiler on the right hand side; thus it loses no heat. The piston rod rises vertically pushing up the big crosshead which is guided by the two large round guide rods. The crosshead extends past the guide rods; two connecting rods from the outside ends of the crosshead drop down to the crank. In the first picture the crank is just visible at the bottom of the picture. The crank is attached to a horizontal shaft running under the engine. The elegant large flywheel is mounted on that shaft on the far side of the engine. In the last photo the flywheel and crank on it can be seen except the crank is not obvious from the angle the picture has been taken at, it is on the spoke. The small water pump is low down in front of the engine in the first photo driven by a rod coming down from a lever attached to the crosshead. A very interesting thing is the pipe running across the top of the boiler from the cylinder to the smoke stack. This is the exhaust steam pipe; it ejects the spent steam vertically inside the exhaust stack which greatly increases the draft through the engine & thus enhances the combustion. An advanced concept that Trevithick pioneered. Besides that the feed water from the pump is pre-heated by the exhaust steam – it is in the large pipe surrounding the exhaust steam pipe (I learned that from a Gutenberg project copy of Scientific American of January 1885 http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14041/14041-h/14041-h.htm )The cylinder is double acting – it is powered on the upward and the downward stroke unlike the single acting engines of Newcomen and Watt.

The exhaust steam pipe going into the smoke stack and water feed is clear in this photo.

In this photo you can just see another advanced feature that Trevithick introduced. At the lower end is the fire grate. There was a tube inside for the fire which bent round and came back to the exhaust smoke stack at the same end , this is called a return flue and doubles the area for the heat to get from the fire into the water.

Those are all the pictures I took of that engine that I pay homage to each time I visit London. I always go up to it and pat it. It is not a visually significant engine and most people don’t realise how it transformed the world. In the background of the last photo you can see the largest steam engine in the museum

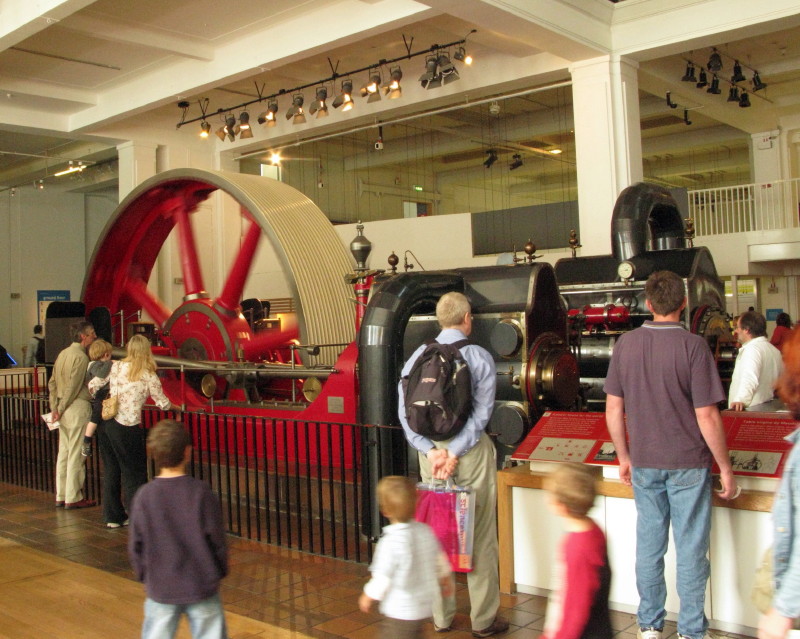

This is it and it was running when I took this photo. That engine was built about 100 years ago.

It is so big I can’t really get a decent photo of it. Quote from www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

Quote:

This mill engine was constructed in 1903 by the Burnley Ironworks Company for Harle Syke Mill in Burnley, Lancashire. Increasingly reliable and efficient steam engines became Britain’s main power source in the later 19th century, driving everything from cotton mills to lawn mowers. At the heart of each factory there was a steam engine like this one. It drove 1700 power looms for weaving textiles at the same time, using a complex system of rotating shafts, pulleys and belts.

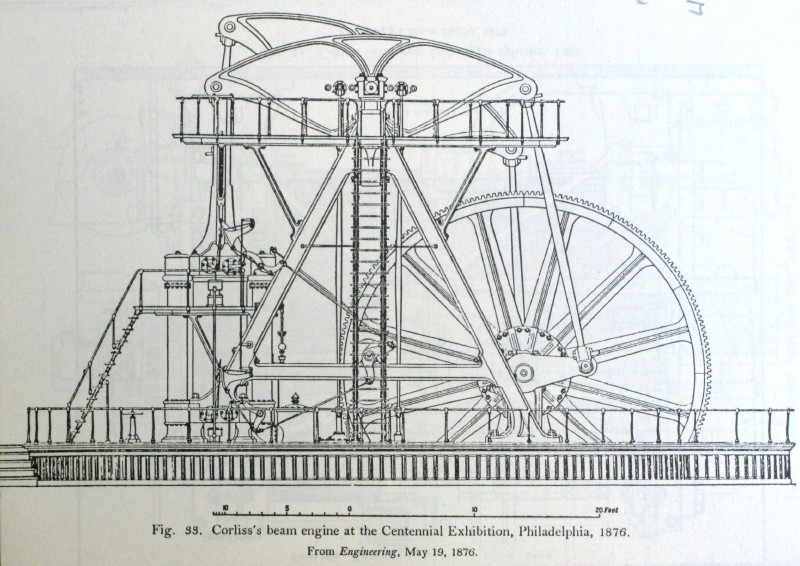

This 700 Horsepower engine has Corliss valve gear. Corliss was an American engineer who designed what I regard as the greatest ever beam engine. The Centennial Engine.

A drawing of it from a book of mine. This is a beam engine as was the original Newcomen engine butthis is the most exquisite one ever in my opinion.

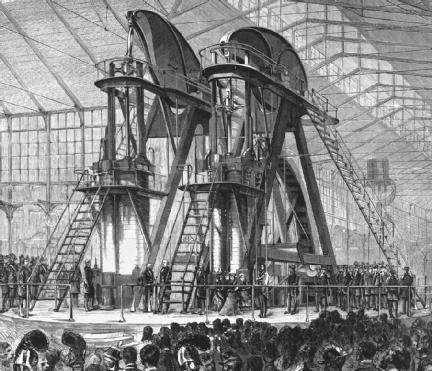

A picture from when it was working.

Quote from http://www.steamtraction.com/archive/2750/

Quote:

The Corliss Centennial Engine is photographed in position within Machinery Hall of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The 700-ton 40-foot tall engine developed 1,400 HP to provide all motive power for the 14 acres of machinery displayed during the six-month Centennial celebration. The 30-foot flywheel revolved at 36 rpm's; the wing-shaped walking-beams were made from 10,000 used horseshoes, which Mr. Corliss thought provided the sturdiest sort of metal available.

The winders on the gold mines on the Reef used steam engines similar to the big one in the Science Museaum (ref http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markham_&_Co. ). When I was at varsity one of the technicians there mentioned to me the difficulty they had adjusting the Corliss valves. Corliss valves were brilliant at improving engine efficiency but you had to understand the principles behind them before you could hope to adjust them correctly and an uninformed mechanic would soon get everything messed up. It is a pity all those beautiful (well to me anyway) old steam engines like the one still running in the Science Museum were broken up when the gold mines converted to electric power winders.

This link has animated steam engines, Newcomen, Watt and Trevithick plus some others but no Corliss; when I first click the individual links the picture is partial but if I close that and ask for the same animation again I get the complete picture (double clicking also seems to help).

http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/on-line/energyhall/theme_See%20the%20engines%20at%20work.asp

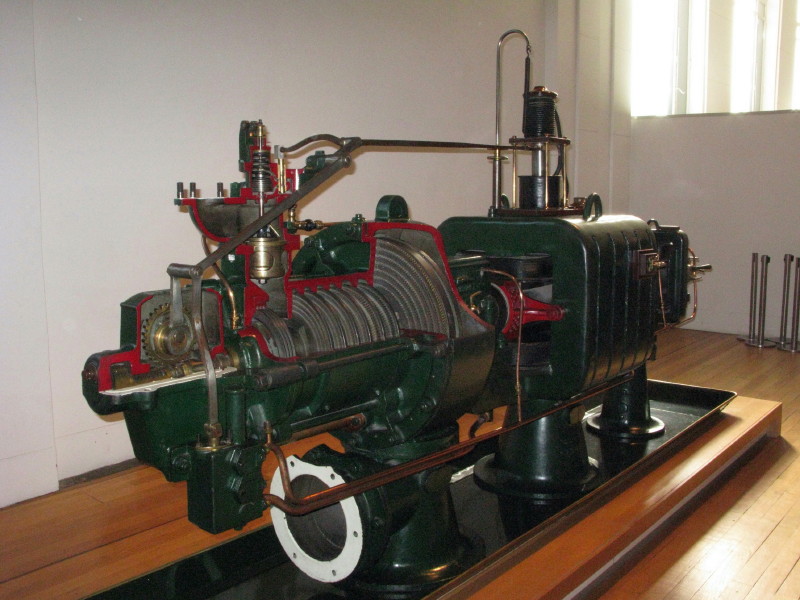

To complete this post I must include this. It is Parson’s steam turbine. The steam turbine rendered reciprocating steam engines obsolete. His first one, made in 1884, is on display in another part of the Science Museum, this particular one was made in 1892. So the steam engine ruled for 175 years before the steam turbine replaced it. About 100 years ago.

So we have a nice sequence here:

300 years ago Newcomen with the first steam engine

200 years ago; Watt engine gives rotating power to drive the Industrial Revolution

200 years ago Trevithick develops high pressure steam engine & first powered train and carriage

100 years ago the end of steam engines as depicted by the big red one here and the start of steam turbines as shown here.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment